Unity and Unreal Engine: Real-Time Rendering VS Traditional 3DCG Rendering Approach

(Revised and updated as of June 2020)

Preamble

Before reading any further, please find the time to watch these. I promise, you won't regret it:

Now let's analyze what we just saw and make some important decisions. Let's begin with how all of this could be achieved with a "traditional" 3D CG approach and why it might not be the best path to follow in the year 2020 and up.

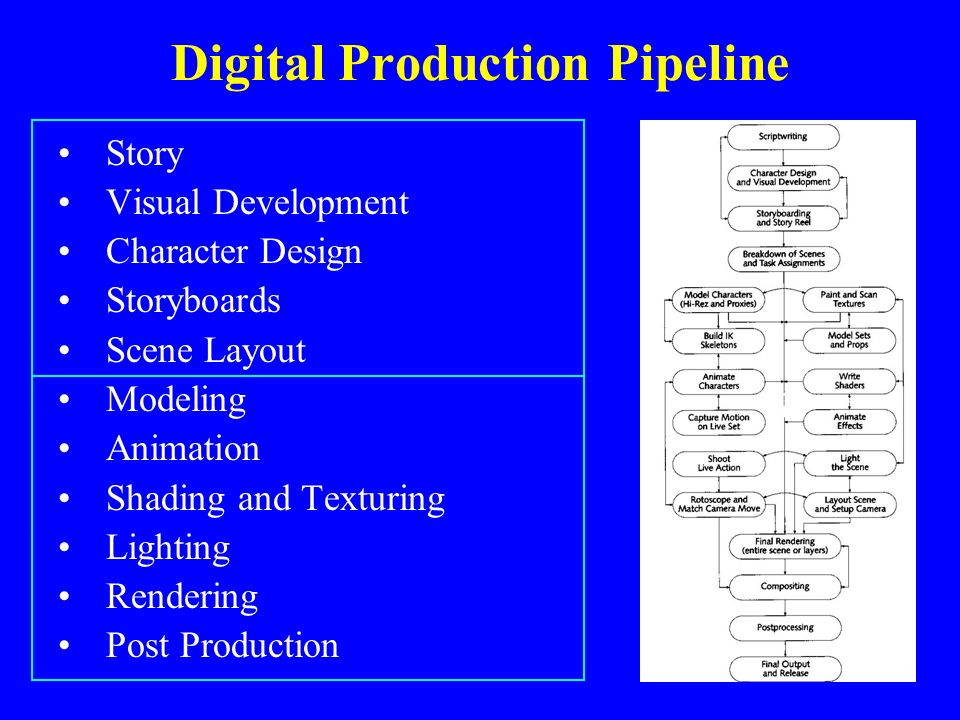

Linear pipeline and the One Man Crew problem

I touched upon this topic in one of my previous posts.

The "traditional" 3D CG-animated movie production pipeline is quite complicated. Not taking pre-production and animation/modeling/shading stages into consideration, it's a well-known fact that an A-grade animated film treats every camera angle as a "shot" and these shots differ a lot in requirements. Most of the time character and environment maps and even rigs would need to be tailored specifically for each one of those.

Shot-to-shot character shading differences in the same scene in The Adventures of Tintin (2011)

Shot-to-shot character shading differences in the same scene in The Adventures of Tintin (2011)For example if a shot features a close-up of a character's face there is no need to subdivide the character's body each frame and feed it to the renderer, but it also means the facial rig needs to have more controls as well as the face probably requires an additional triangle or two and a couple of extra animation controls/blendshapes as well as displacement/normal maps for wrinkles and such.

But the worst thing is that the traditional pipeline is inherently linear.

Thus you will only see pretty production-quality level images very late into the production process. Especially if you are relying on path-tracing rendering engines and lack computing power to be able to massively render out hundreds of frames. I mean, we are talking about an animated feature that runs at 24 frames per second. For a short 8-plus-minute film this translates into over 12 thousand still frames. And those aren't your straight-out-of-the-renderer beauty pictures. Each final frame is a composite of several separate render passes as well as special effects and other elements sprinkled on top.

Now imagine that at a later stage of the production you or the director decides to make adjustments. Well, shit. All of those comps you rendered out and polished in AE or Nuke? Worthless. Update your scenes, re-bake your simulations and render, render, render those passes all over again. Then comp. Then post.

Sounds fun, no?

You can imagine how much time it would take one illiterate amateur to plan and carry out all of the shots in such a manner. It would be just silly to attempt such a feat.

Therefore, the bar of what I consider acceptable given the resources available at my disposal keeps getting...

Lower.

There! I finally said it! It's called reality check, okay? It's a good thing. Admitting you have a problem is the first step towards a solution, right?

Right!?..

Oups, wrong picture

Oups, wrong pictureAll is not lost and it's certainly not the time to give up.

Am I still going to make use of Blend Shapes to improve facial animation? Absolutely, since animation is the most important aspect of any animated film.

But am I going to do realistic fluid simulation for large bodies of water (ocean and ocean shore in my case)? No. Not any more. I'll settle for procedural Tessendorf Waves. Like in this RND I did some time ago:

Will I go over-the-top with cloth simulation for characters in all scenes? Nope. It's surprising how often you can get away with skinned or bone-rigged clothes instead of actually simulating those or even make use of real-time solvers on mid-poly meshes without even caching the results... But now I'm getting a bit ahead of myself...

Luckily, there is a way to introduce the "fun" factor back into the process!

And the contemporary off-the-shelf game engines may provide a solution.

Film production and the upcoming blog post series

As promised, I will do my best to document each and every step of the process of the short animated film production (for archival purposes of course, for no one should ever take some weekend scientist's ramblings seriously).

Therefore, I'm starting a series of blog posts under the "Production" category I will gradually fill with new articles along the way.

Preliminaries

Film production is not a new experience for me. I've produced and directed several short films and a couple of music videos over the years with my trusty line of Canon EOS cameras, starting with the very first entry-level EOS 550D capable of recording full HD 24p video.

It has long been superseded by a series of upgrades and as of today - with EOS 750D with a Cinestyle Profile and the Magic Lantern firmware hack.

I have a bit of practice working the cameras including rentals such as RED and Black Magic, the gear, all kinds of lenses, some steady-cams, cranes, mics and such.

Long story short, I produced a couple of stories, which at some point led me to a series of videos for a client that called for a massive amount of planar and 3D-camera tracking, chroma-keying, rig removal and, finally, an introduction of CG elements into footage. It felt like getting baptized by fire and in the end it was what made me fall in love with VFX and ultimately – 3D CGI.

Now what does this have to do with the topic of pure CG film production?

How and why it's different

In traditional cinema you write the script, plan your shots, gather actors and crew, scout locations, then shoot your takes and edit and post, and edit and post, until you're done. You usually end up with plenty of footage available for editing, if you plan ahead well. This is how I've been doing my films and other videos for a long time.

Animated feature production is vastly different from traditional "in-camera" deal. Even if we're talking movies with a heavy dose of CGI (Transformers, anyone?) it's not quite the same since even in this case you're mostly dealing with already shot footage whereas in CG-only productions there's no such foundation. Everything has to be created from scratch. Duh!

The first CG-only "animation" I've produced up to this day was a trailer for my iOS game Run and Rock-it Kristie:

Here I had to adapt and change the routine a bit, but even then 80% of the footage was taken from three special locations in the game I built specifically for the trailer. So basically the trailer was "shot" with a modified in-game follow-camera rig with plenty of footage available for me to edit afterwards.

In a way it was quite close to what I've well gotten used to over the years.

The process

As soon as you decide to go full retard CG, boy of boy, are you in trouble.

Since I'm not experienced enough in the area of animated CG production I'll give a word to Dreamworks and their gang of adorable penguins from the Madagascar and let them describe in detail what it takes to produce an animated film:

Wow that's a lot of production steps...

So in the long run you are free to create your own worlds, creatures and set up stories and shots completely the way you want them to be, the possibilities are limitless. The pay-off is obviously a much more complicated production process which calls for lots of things one often takes for granted when shooting with a camera: people, movement, environments and locations, weather effects and many more objects and phenomena that are either already available for you to capture on film or can be created either in-camera or on set and in post.

Hell, even when it comes to camera work, if you don't have access to the sweet tech James Cameron and Steven Spielberg use when "shooting" their animated features (Avatar, The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn, respectively) you'll have to animate the camera in your DCC or shoot and track real camera footage for that sweet handheld- or steadycam-look.

Scared yet?

So, all things considered I should probably feel overwhelmed and terrified at what lies ahead. Right?

Nope.

It's a just a Project. And as project manager I thrive on challenge and always see every complication as a chance to learn new skills and follow each and every project to the end. And this one will be no different.

Thank you for reading and stay tuned!